by Peter Wagner,

June 14, 2004

On June 7, talks between the New York State Senate and the Assembly on how to best reform the draconian Rockefeller Drug Laws broke down. Publicly, the dispute is over ideological disagreements, but an obscure Census quirk that counts prisoners as residents of the prison’s legislative district may be responsible for distorting how the debate is framed.

The Assembly wanted to reduce a broad range of drug sentences while the Senate wanted to focus only on the most extreme sentences. Previous columns (May 24, 2004 and December 1, 2003) have profiled the district of the Senator’s lead negotiator, Dale Volker. This column examines the district of another member of the Senate’s delegation to the conference committee, Crime Committee Chair Senator Michael Nozzolio.

The 54th District Seneca Falls Republican explained the Senate’s perspective at the start of the meetings: “Our focus is on the victim, not the drug dealer.” The Assembly members took the opposite approach, arguing that drug crimes are victimless crimes and should have sentences shorter than those imposed for violent acts.

An analysis of Senator Nozzolio’s district suggests that his opposition to a thorough repeal of the Rockefeller Drug Laws may not lie just in ideology but in an obscure Census quirk that counts prisoners as if they were residents of the prison town. Because 65.5% of New York State’s prisoners are from New York City, but only a few small prisons exist within the city, 43,740 city residents are counted as upstate residents. This swells the political power of upstate legislators and their real constituents while diluting the clout of New York City’s residents.

Continue reading →

by Peter Wagner,

June 7, 2004

Many prison town officials are quick to claim prisoners as residents when the Census Bureau comes to town, but prisoners report that this is the only time these officials are so welcoming.

The Census Bureau counts the nation’s mostly urban prisoners as if they were residents of the prison town. When the Census’ only purpose was to count the total population of each state for purposes of apportioning Congress, this procedure might have made sense. Today, when this data is used for state legislative redistricting, the method is an outdated relic that distorts the size of communities within the same state. Last week’s column discussed the theoretical rationale for defining residence based on the place you willingly choose to be and argued that since prisoners are moved to prison against their will, their residence is unchanged. In prior columns, I’ve written that most states have constitutional clauses and statutes that define residence for electoral purposes as to exclude prisons. This column explores how communities with prisons conceive of prisoner residence.

In the cases where the Census Bureau erred and placed the prison in the wrong rural town, the town with the prison frequently complained. But outside of the Census, do local officials consider prisoners to be residents of the town? Are there local services that are available only to residents that prisoners are denied on the basis that the prisoners are not residents?

To find out, I placed classified ads in publications that prisoners read and was flooded with responses. Many prisoners were intrigued, but stumped. This letter was typical:

“Albion State Penitentiary [where I am incarcerated] is so far out in the woods, in the extreme northwest corner of Pennsylvania, it is known as Far B Yon. … I’d be pleased to help … but I have no idea what organizations or types of services to request assistance for.”

By virtue of their incarceration, prisoners are not able to visit the local parks or discuss the affairs of the day in the town square, but my correspondents did identify two local services applicable only to residents but denied to them: the local library and the court system.

Continue reading →

by Peter Wagner,

May 31, 2004

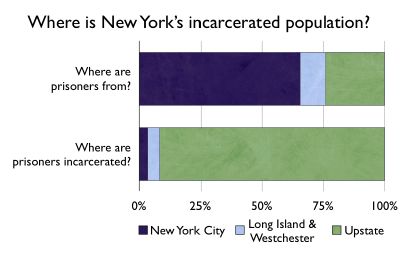

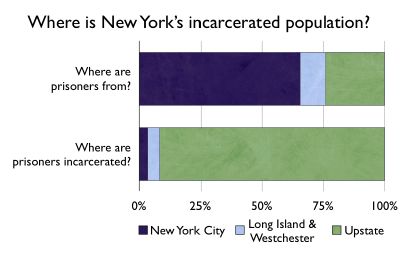

In the words of U.S. Department of Agriculture demographer Calvin Beale: “A rural prison is a classic ‘export’ industry, providing a service for the outside community.” Although rural counties contain only 20% of the national population, they have snapped up 60% of new prison construction. Like export processing zones in Third World countries, even the raw material is imported for final manufacture. In New York, for example, only 24% of prisoners are from the upstate region, but 91% of prisoners are incarcerated there.

The Census Bureau counts the nation’s mostly urban prisoners as if they were residents of the mostly rural towns that host the prisons. This methodology infects the data used for legislative redistricting and results in a dilution of the voting strength of the communities that have large numbers of people in prison. States with large prison populations violate the 14th Amendment’s One Person One Vote principle when they rely on Census Bureau data to draw their legislative districts.

Continue reading →

by Peter Wagner,

May 24, 2004

The current legislative stalemate in reforming New York’s drug laws might be the result of a Census Bureau quirk that counts prisoners as if they were residents of the prison town. Senate conference co-chairman Dale Volker is a former police officer opposed to many of the reforms proposed by Assembly conference co-chair Jeffrion Aubry of Queens. Aubry used to lead a social service agency that provided drug treatment.

Something else is reducing the clout of advocates for drug law reform: The U.S. Census. Each Senate district in New York City is missing about 1,800 incarcerated residents, with these residents instead credited to rural districts like Senator Dale Volker’s. One out of every 25 adults in Volker’s district is a prisoner barred by law from voting for or against the Senator. By the time these prisoners complete their sentences and are again allowed to vote, they will be back home in a different district.

The six prisons in Volker’s 59th district contain 8,951 prisoners including 2,391 drug offenders. These bodies swell Volker’s influence in violation of the Constitutional guarantee of one-person-one-vote. Prisons are big business in only a few districts, but every district in the state that sends people to prison sees its clout diminished in the legislature as a result of the Census Bureau’s counting method. Senator Volker has the right to advocate against drug law reform if he wishes, but his political clout should be based on the actual number of his rural constituents, and not on how many of New York City’s drug addicts are temporarily in rural prisons.

Source: Michael Cooper, Republicans and Democrats Clash on New York Drug Laws, New York Times, May 21, 2004 and Peter Wagner, Counting urban prisoners as rural residents counts out democracy in New York Senate Prison Policy Initiative, PrisonersoftheCensus.org December 1, 2003.

by Peter Wagner,

May 17, 2004

I was recently asked if restoring a prisoner’s right to vote would solve the census counting problem. Personally, I think that would be a good idea, but it would not address the principal problem from miscounting the incarcerated: diluting the votes of prisoners’ home communities.

All states that allow or recently allowed prisoners to vote required them to do so back home via absentee ballot. Most states have constitutional clauses or statutes that say that incarceration does not change a residence. (See for example New York, Arizona, Michigan, Vermont and Maine.) If prisoners were to be allowed to vote, it would be back home. Letting prisoners vote is controversial. Where they would vote is not.

The real victims from the way the Census counts prisoners are prisoners’ family and neighbors — people who have not been convicted of anything. Counting the incarcerated not at their homes but in radically different communities dilutes the votes of all the residents of the home communities.

There are 3 potential solutions:

- The Census Bureau can change its “usual residence rule” to count prisoners at the address they declare or at their last known address. The Census wrote the rules and they can change them. In the past, the Census has changed how numerous groups were counted, including college students, missionaries, and overseas Americans.

- States can fix the Census data before conducting redistricting. New York fixed some Census Bureau mistakes that placed some prisons in the wrong rural county. Kansas’ constitution requires that out-of-state students and military be deducted and in-state students and military restored to their homes. The Kansas Secretary of State sends out a survey to the colleges and military bases, and then fixes the data before giving it to the Legislature for redistricting.

- States can do their own censuses. Many states used to do this. Massachusetts was the last to abolish the state census, in about 1990. New York’s Constitution talks about bringing back the state census if the federal census does not contain the necessary data. Counting prisoners in the wrong part of the state sounds like deficient data to me.

The best solution is the first one. The Census should just update the usual residence rule to count the incarcerated at home. The rule might have made sense in 1790 when incarceration was low and redistricting didn’t exist, but it’s a relic now.

by Peter Wagner,

May 10, 2004

The Bureau of Justice Statistics provides incarceration rate data for Latinos, non-Latino Whites, and non-Latino Blacks, but it does not provide this data for other groups. For another Prison Policy Initiative project, we tried to use the Census 2000 data to fill in this gap for every state in the country, but the results were not what we expected, and one finding was so shocking that we had to investigate further.

According to Census 2000 data, Minnesota appears to incarcerate Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders at a rate 45.8 times higher than it incarcerates White people. By Bureau of Justice Statistics figures, Minnesota has the 4th highest racial disparity between Black and White incarceration rates, incarcerating Blacks at a rate almost 13 times as frequently as Whites.

Why would Native Hawaiians in Minnesota be treated so harshly? Could it even be true that the Minnesota has incarcerated 1 out of every 10 Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders in the state?

Continue reading →

by Peter Wagner,

May 3, 2004

Census 2000 showed a number of rural counties in the West, Midwest and Northeast that more than doubled their Black populations over the previous decade. Is this some sort of reversal of the great migration that saw millions of Blacks leave the rural South for Northern cities? Is a new economic opportunity drawing Blacks to leave cities for rural places? Not quite.

Most of the counties shown by the Census Bureau to have the fastest growing Black populations (see counties marked in purple in the first map below), are counties with new prisons with large incarcerated Black populations. (Compare with second map below.)

The Census Bureau counts incarcerated people as if they were residents of the prison town, even though prisoners have no contact with the outside community and are not there by choice. This methodology has staggering implications for how and where Black citizens are counted. On Census Day, 2.5% of Black Americans found themselves behind bars. Twelve percent of Black men in their 20s or early 30s are incarcerated. These figures are 7 to 8 times higher than the corresponding statistics for Whites. The Census Bureau’s method of counting the incarcerated disproportionately counts Blacks in the wrong place.

Continue reading →

by Peter Wagner,

April 26, 2004

Counting incarcerated people as if they were residents of the prison town leads to misleading portrayals of which counties are growing and which are declining. Declining populations in a county are often a sign of economic distress. Census 2000 reported that 78% of counties experienced population growth during the 1990s. Yet 56 of these counties can attribute their growth only to prison expansion and not to children being born or new residents choosing to move to the county. Said another way, for each 50 counties labeled by the Census as growing during the 1990s, one of those counties actually saw a decline in their actual free population. (See map and table.)

Continue reading →

by Peter Wagner,

April 22, 2004

Alan Elsner’s new book on the U.S. prison system, Gates of Injustice: The Crisis in America’s Prisons includes a call for reforming how the U.S. Census counts prisoners. Counting prisoners in the facility town and not at home is discussed in Chapter 10 about rural prisons and is included in Chapter 12’s list of “Some Modest Suggestions”:

“The way in which the Census Bureau counts inmates as citizens of the jurisdictions where they are jailed for purposes of drawing political boundaries or awarding federal grants seems like a clear case of inequity…. Fixing this would send a strong signal of the nation’s continued commitment to social justice.”

Source: Alan Elsner, Gates of Injustice: The Crisis in America’s Prisons, Prentice Hall, 2004, p. 221.

by Peter Wagner,

April 19, 2004

Counting large external populations of prisoners as local residents leads to misleading conclusions about the size and growth of communities. Many of the prison hosting counties have relatively small actual populations, but large prison populations. Twenty one counties in the United States have at least 21% of their population in prison. (See map and table.) In Crowley County, Colorado and West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana, one-third of the population consists of prisoners imported from somewhere else.

Continue reading →