We explore state redistricting reports to show that, despite facing immense challenges, states were remarkably successful ending prison gerrymandering after the 2020 Census.

by Mike Wessler and Aleks Kajstura,

June 10, 2024

During the 2020 redistricting cycle, more than a dozen states took it upon themselves to do what the Census Bureau has refused: end prison gerrymandering. Through their redistricting process, they worked to unwind the flawed way the Bureau counts incarcerated people — as residents of a prison cell — and instead count them where they actually live, creating legislative districts that more accurately reflect actual resident populations.

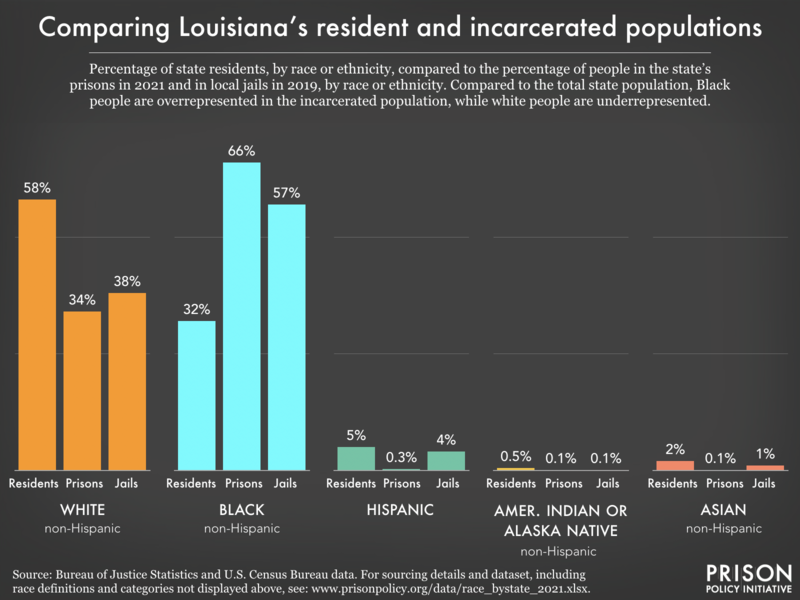

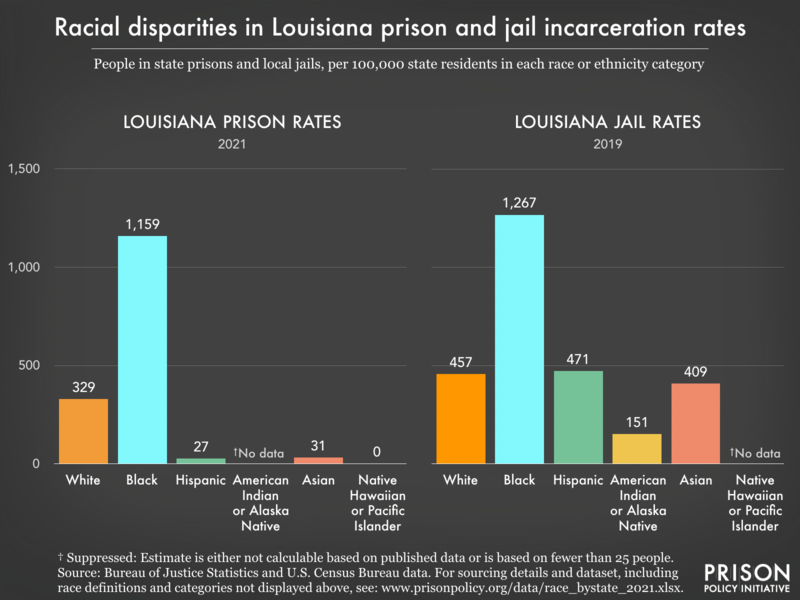

Prison gerrymandering is a problem created because the Census Bureau counts incarcerated people as residents of a prison cell rather than at their true communities. When states then use Census data during their redistricting process, they artificially inflate the population of prison communities and give them a larger voice in government.

With such rapid growth in the movement to address prison gerrymandering, it is natural to wonder: How successful were these states? How many people were they able to count at their home addresses?

It is an important question with huge implications; 19 states are already poised to adjust their redistricting data to address prison gerrymandering in the 2030 redistricting cycle. These questions can help states evaluate how they can do better during the 2030 redistricting cycle. It can guide states that haven’t yet adopted anti-prison gerrymandering laws but are considering them. Finally, it can illustrate how states are limited in their ability to solve this problem in ways the Census Bureau is not.

To answer these questions, we reviewed redistricting reports and data from 13 states that addressed prison gerrymandering after the 2020 census to understand how many people in state prisons they attempted to count in their home communities and how many they were able to reallocate successfully.

Perfection isn’t possible, so it’s not the goal

Before diving into our analysis, it is important to remember that it is impossible and unrealistic for states to successfully reallocate everyone in their prisons to their home communities.

There are three primary reasons why a state can’t count an incarcerated person at their home address:

- The person’s last address is in a different state: States don’t have the power to reallocate people across state lines, so they cannot count people from out of state in their home community.

- The state has decided not to reallocate an incarcerated person for a policy-based reason: Unfortunately, some states have implemented arbitrary limitations on their reforms by excluding certain incarcerated people from being counted in their home communities. For example, Rhode Island did the mapping work for all people incarcerated in the state correctional facilities. However, it chose to count incarcerated people with more than two years left on their sentence at the prison location in the redistricting data. While we and other organizations think this is misguided, it is the choice policymakers have made, so redistricting staff could not count them in their home community.

- Erroneous or missing data: State redistricting officials often rely on their Department of Corrections (DOC) to get address data for incarcerated people. Generally, that data contains everything they need to implement their reforms. However, sometimes data is missing or erroneous. Apart from typos and other record-keeping errors in home address data, there are a few situations where home addresses are missing altogether. For example, if an incarcerated person indicated they were unhoused before coming to prison, the DOC will likely leave the address field blank or note “homeless.” This may be an appropriate response for prison staff, but it creates problems for redistricting officials.1While there are some steps redistricting officials can take to reduce this number, it often takes time, which is something they don’t have much of.

These limitations make it impossible for a state to reallocate 100% of people in its prisons to their home communities, so when they evaluate their success, they shouldn’t grade themselves against perfection. Instead, they should ask themselves: “Of the people it was possible to reallocate, how many did we reallocate?”

How did states do?

For our analysis, we looked at two key numbers:

- The state’s success rate for reallocating people that it was possible to count at home.2

- The total percentage of people in state prisons counted at their home address.

Our analysis 3 shows that most states did remarkably well. This is noteworthy because 2020 was a notoriously difficult redistricting cycle, in which Census data was delayed, and many states adopted prison gerrymandering reform laws late in the decade.

Of the 13 states we analyzed, 10 published their methodology. Nine out of 10 were able to reallocate at least 80% of people with addresses that met the states’ criteria, with Nevada being the lone exception. Impressively, California successfully mapped every address that it attempted.

2020 redistricting state reallocation success rates

| State |

Success rate for reallocating people who’s address met the state’s criteria |

Percentage of people in state prisons successfully counted at their home address |

| California |

100.0% |

99.7% |

| Colorado |

88.5% |

82.1% |

| Connecticut |

96.9% |

87.6% |

| Delaware |

85.5% |

79.2% |

| Maryland |

84.8% |

77.0% |

| Montana |

96.3% |

45.3% |

| Nevada |

68.9% |

64.1% |

| New Jersey |

95.3% |

89.5% |

| New York |

91.9% |

91.9% |

| Pennsylvania |

State did not publish methodology |

60.6% |

| Rhode Island |

83.1% |

41.0% |

| Virginia |

State did not publish methodology |

88.2% |

| Washington |

State did not publish methodology |

91.4% |

States were so successful that even in two of the three states where we could not fully analyze the success rate because they didn’t publish their methodology — Virginia and Washington — we can tell that roughly 90% of their total state prison population was successfully reallocated to their home communities. Importantly, like Rhode Island (which we explained above), Pennsylvania also made a policy choice to exclude certain incarcerated people from these reforms, instantly lowering the portion of its prison population that could be counted at home.

Getting to 100%

While states have done a remarkable job implementing these reforms, every incarcerated person should be counted in their home communities for redistricting purposes. What can government officials do to accomplish this?

- Start collecting, assessing, and cleaning data early: Getting good data from the Department of Corrections is critical to successfully implementing reforms. That’s why state redistricting officials should work with that agency now to ensure it is collecting the data they’ll need during the next redistricting cycle. Similarly, states that haven’t yet addressed prison gerrymandering should adopt and implement policies to do so now. This will ensure prisons collect and maintain high-quality address data for people they incarcerate.

- Don’t adopt arbitrary limitations on reforms: When adopting anti-prison gerrymandering reforms, states should include all incarcerated people, regardless of the length of their sentence. Even if a person is likely to spend decades behind bars, they’re still not a resident of the legislative district that contains the prison 4 — they don’t have ties to that community, they don’t call it home, and if they have a problem that they want lawmakers to fix they’re not likely to call the legislator who represents the prison but rather the elected officials from their home community — so the town containing the prison shouldn’t get an outsized voice in government simply because the facility happens to be located there.

- The Census Bureau must change its policies: Even if states do everything in their power to address prison gerrymandering, there will still be some incarcerated people that they can’t count in their home districts, most frequently those who come from different states. Similarly, but not covered in this analysis, if a state contains a federal prison, redistricting officials cannot reallocate those incarcerated people to their home communities. The Census Bureau is the only government entity with the power to address this problem completely and across state lines.

This analysis shows that states have been incredibly successful in implementing reforms to address prison gerrymandering. History suggests that if the Census Bureau fails to resolve this problem, states will do even better during the 2030 redistricting cycle. This should give confidence to places considering similar reforms and motivate them to take action now.

Ultimately, though, to fully address prison gerrymandering, the Census Bureau should listen to the growing bipartisan consensus among states and adjust its policies to end prison gerrymandering nationwide.

Methodology

We measured the states’ success in two different ways:

- Success rate for reallocating people who met the state’s criteria for reallocation

- Total percentage of people in state prisons successfully counted at their home address

It is worth noting that we only provided partial analyses for three states that have ended prison gerrymandering for the following reasons: Pennsylvania and Virginia have not made their methodologies publicly available; Washington has some documentation available, but it does not provide the number or percentage of people successfully reallocated, or the total prison population the state began with.

Our state-specific methodologies are below.

California

The state documentation reports a total of 122,730 people in state prisons across the state (MacDonald presentation, p. 4). Ultimately, the adjusted dataset includes 122,393 people in state prisons who were successfully reallocated home in California (Statewide Database). Based on the 122,393 successfully reallocated people, we can assume that the remaining 337 people had a last known place of residence outside of California or an address that “cannot be determined” (Final Maps Report, p. 20). These people were counted in an “unknown geographical location” and excluded “from the population count for any district, ward, or precinct” (Final Maps Report, p. 20).

State documentation:

Colorado

The Colorado state documentation reports 17,506 people in prisons across the state. This does not include any people in federal prisons.5

1,270 people in state prisons reported a known previous address outside of the state and, therefore, were counted at the facility (p. 3). 6

That leaves a remaining 16,236 people in prison with Colorado addresses. 1,872 of those people in state prisons with in-state addresses had unusable addresses and were subsequently counted at the facility (p. 3). The state defined “unusable” as addresses with “no or incomplete street address information” or people who reported being homeless before incarceration (p. 3).

The remaining 14,364 people in state prisons could be reallocated home in Colorado (p.3).

Connecticut

The Connecticut state documentation states the Department of Corrections reported a total of 11,853 people in state prisons across the state (p. 4). An additional 1,057 people were in federal prisons and subsequently counted at large (p.4).

392 records had incomplete or unusable addresses and were subsequently counted at large (p. 5). The reasons for these 392 unusable addresses were listed as: 301 records did not include a street address, 75 records did not have a street number, four records listed a PO box in the street address field, eight records listed “an apartment complex where the precise address location and [Census] block could not be determined,” and four records were for “temporary locations (e.g., hotel, shelter, or campground) where the precise census block location could not be determined” (p. 5). 687 records had an out-of-state address and were subsequently counted at large (p. 4). 7 10 records were for people serving life-without-parole sentences and subsequently counted at the facility. 49 records were for people under 18 years old and were “excluded” (p.3).

Of the remaining 10,715 records, 333 “could not be geocoded in cleaned dataset” (p. 7). 8 The remaining 10,382 people in state prisons were successfully reallocated home in Connecticut (p.6).

Delaware

The Delaware state documentation reports that a list of records from the Department of Corrections included 4,748 records (p.3). 350 of these records were for out-of-state addresses and were excluded from the counts of the facility and the population totals (p. 3). There were 4,398 remaining in-state addresses. 637 of these records were “without a good geocoded home address” and were counted at the facility (p. 3). The remaining 3,761 people in state prisons could be reallocated home in Delaware (p.3).

Maryland

The Maryland state documentation reports a total of 19,802 people in prisons across the state (p. 1). This does not include any people in federal prisons. 1,821 of those people had out-of-state addresses and were not counted. That leaves a remaining 17,981 people with in-state residence. Out of those 17,981 people, 2,793 people had “no address” – meaning they did not have “a valid prior address or they did not provide a previous residential address” (p. 1) – and were subsequently counted at the facility. The remaining 15,242 people in state prisons could be reallocated home in Maryland.

Montana

The Montana state documentation reports 2,840 people in state prisons (p. 5). 1,505 were deemed “not appropriate for reallocation,” which included: 1,389 records with no addresses, 56 with out-of-state addresses, 28 with addresses in jails or other similar facilities, 20 indicating “transience,” and 12 with P.O. boxes as addresses (p. 5). The remaining 1,335 people in state prisons had addresses deemed “appropriate for geocoding” (p. 2). 1,286 were successfully geocoded, and 49 were not geocoded, therefore excluded from reallocation (p. 2).

Nevada

The Nevada state documentation reports 12,214 records of people in Nevada state prisons (Killian presentation, p. 3). 860 of these addresses were for out-of-state residences and were not counted (Killian presentation, p. 9). This leaves 11,354 records with in-state addresses. Ultimately, the adjusted dataset includes 7,826 people in state prisons who were successfully reallocated home (Nevada Reapportionment and Redistricting website). Based on the 7,826 successfully reallocated people, we can assume that the remaining 3,528 people had addresses that could not be reallocated. The available documentation does not explain why some addresses could not be reallocated.

State documentation:

New Jersey

The New Jersey state documentation reports a total of 18,109 people in state prisons (p. 3). An additional 4,067 people are in federal prisons and were subsequently counted at large (p. 10). 9

Out of the 18,109 people in state prison, 1,114 people had out-of-state addresses. 10

Of the remaining 16,995 people in state prisons with in-state addresses, 797 had in-state addresses that were unusable (p.5). The state defines “unusable” addresses as: residential addresses that were unknown/homeless, incomplete, PO boxes, rural route addresses, or contained an invalid/nonexistent address or street name.

The remaining 16,198 people in state prisons could be reallocated home in New Jersey (p.5).

New York

The New York state documentation (p.2) reports a total of 46,418 people in prisons across the state. 3,926 of those people are in federal prisons and were subsequently counted at large. That leaves a remaining 42,492 people in New York state prisons. The three-step geocoding and address verification process used in New York included the following:

- Utilization of the Google Maps Geocoding API 12 to extract the latitude and longitude coordinates from addresses. At this point, geocoding results were accepted when the program confirmed street address precision. These results were then converted to Census blocks.

- Reverse geocoding the information generated by the Google Maps Geocoding API latitude and longitude points to a mapped address, and then these results were manually compared to the original addresses. Discrepancies at this stage were investigated using Google StreetView, Bing Maps, and street name lists.

- At this point, any remaining “invalid addresses” (i.e., addresses that were not successfully mapped to an address) were investigated manually using Google StreetView, Bing Maps, and street name lists. The state reports that “many of these initially invalid addresses were effectively geocoded” at this point by visually confirming house and building numbers or rectifying street name misspellings. Google StreetView and Bing Maps had poor coverage or limited visibility for some apartment complexes and trailer parks. In these instances, a third source was used, the Cornell University-based New York Block Browser LUCA Evaluation System (NYBBLES), allowing for rooftop geocoding of many individual structures in mobile home parks and apartment complexes.

After these three steps, 3,465 of those people in state prisons still had “invalid” addresses and were subsequently counted at large. Invalid addresses were loosely defined in the documentation (p. 2-3) as addresses that were not able to be geocoded successfully via New York’s three-step process. 39,027 people in state prisons were able to reallocated home in New York.

Rhode Island

The Rhode Island redistricting consultant’s documentation reports 2,618 people in Rhode Island Department of Corrections custody across the state (Nov. 15 presentation, slide 13). 691 addresses had “obstacles to geocoding,” which included: 271 records with no permanent addresses, 154 with out-of-state addresses, 146 serving home confinement,11 44 incarcerated out of state, 23 addresses listed at the facility, 10 addresses with no street, and 4 with P.O. boxes as addresses (Nov. 15 presentation, slide 13). The remaining 1,927 people in custody had addresses that were deemed geocoded (Jan. 12 presentation, slide 3).

While 1,927 addresses were successfully geocoded, the Rhode Island redistricting process only reallocated people who were not yet sentenced or had less than two years until their expected release date. Out of all 1,354 people (Jan. 12 presentation, slide 3) in Rhode Island Department of Corrections custody who met that criteria, only 1,074 people were reallocated to their home address.

State documentation:

Read the entire methodology