Incarceration in America: Past and Present: A Panel with Three Leading Scholars

Historian and PPI board member Heather Thompson gave an overview of how prison gerrymandering distorts Pennsylvania democracy, and showed the graphic from our brand new report "Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie."

by Peter Wagner, April 9, 2014

Last night, I attended a fascinating panel at Yale, “Incarceration in America: Past and Present: A panel with Three Leading Scholars.” Presenting were

Khalil Gibran Muhammad, NYPL Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture; Caleb Smith, Professor of English, Yale University and Prison Policy Initiative board member Heather Ann Thompson, Associate Professor of History, Temple University.

The Moderator was David Blight, Director of Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition.

The event’s summary:

The three scholars [discussed] the history and impact of incarceration in the US — from imprisonment and ideas about prisons in the 19th Century, to the increasing connections between race, social science and criminality in the early 20th Century, to late 20th and 21st Century mass incarceration.

And here, Heather used our new briefing, Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie:

In her talk, Heather also used a map from our report on prison gerrymandering in Pennsylvania and received a lot of shocked and outraged responses from the moderator and the audience about how the Census Bureau’s prison count distorts democracy.

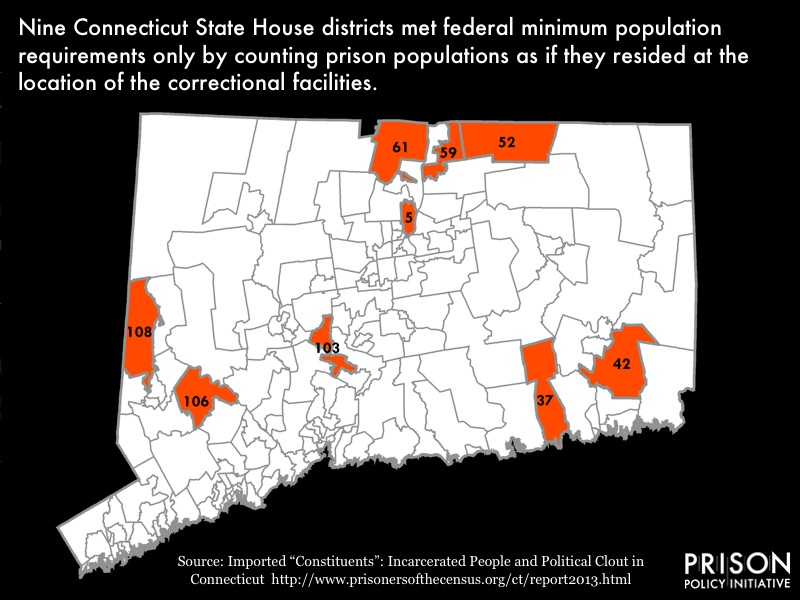

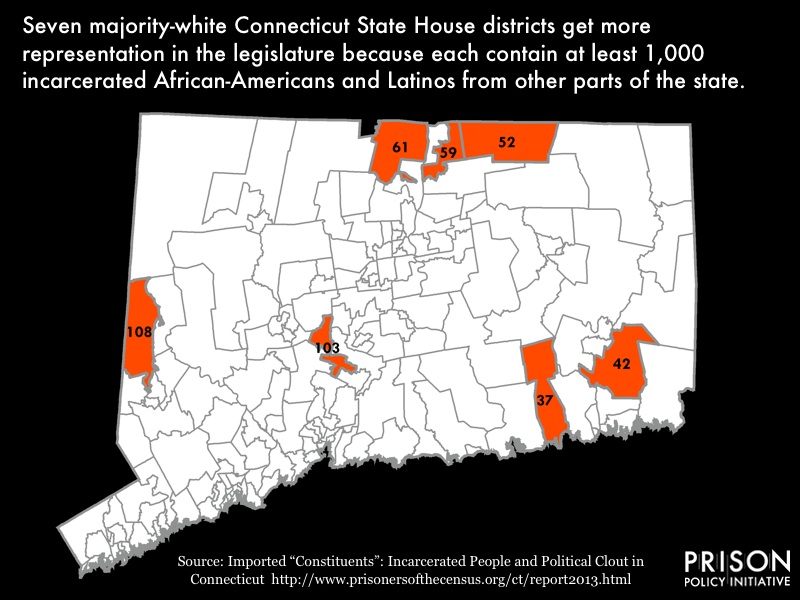

I should have shared them with Heather before the talk, but we’ve also produced some maps illustrating our research in Connecticut that weren’t included in our 2013 report:

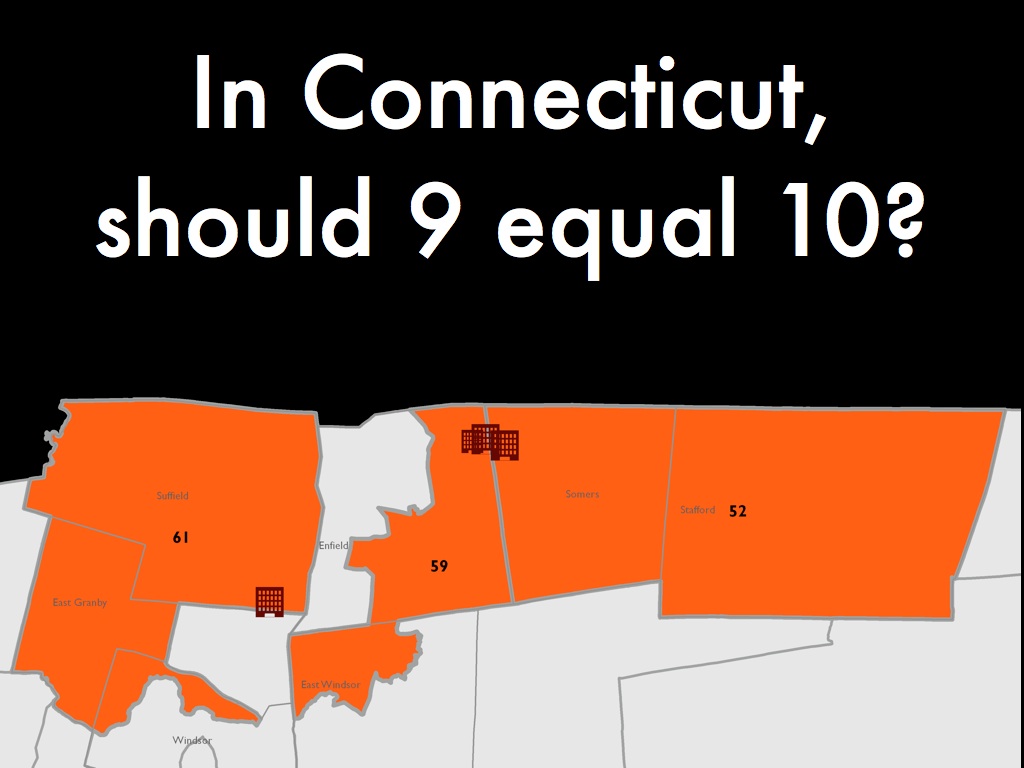

Connecticut provides one of the more dramatic instance of prison gerrymandering in the nation. There are three districts where about 10 percent of the population is actually made up of incarcerated people from elsewhere in the state. In all three districts, more than half of the reported African-American population is actually incarcerated:

For more on prison gerrymandering in Connecticut see our Connecticut campaign page.

* * *

Note: District 52 is 9.9% incarcerated and 87.4% of the African-American population in the district is incarcerated. District 59 is 13.9% incarcerated and 71.7% of the African-American population in the district is incarcerated. District 61 is 9.1% incarcerated and 59.0% of the African-American population in the district is incarcerated.