“Prison Gerrymandering in Massachusetts” report reveals phantom constituents at town meeting

New report reveals prison gerrymandering at town meeting in 7 Massachusetts towns.

October 30, 2013

For more information contact:

Aleks Kajstura

(413) 527-0845

Easthampton, Mass. – Chances are, if there’s a prison on the other side of town, your voice in town affairs is muffled.

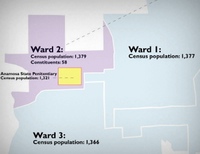

Why? Because the Census Bureau counts incarcerated people at prison locations—where they neither vote nor reside— rather than at their home addresses. When governments use this data to draw electoral districts, they grant undue political power to people who live near prisons and dilute the votes cast everywhere else. Although not always intentional, this “prison gerrymandering” often results in significant voting inequality. A new report from the Prison Policy Initiative, reveals that the Census Bureau’s counts of incarcerated populations lead 7 Massachusetts towns to dilute the votes of residents who do not live in the precinct that contains a correctional facility.

In both Ludlow and Plymouth, for example, 35% of a precinct’s representatives at town meeting are attributed to the jail population. That gives any 65 people who live in those precincts the same voice at town meeting as 100 residents from any other precinct.

These phantom constituents inflate the voice of the actual residents of that precinct and in turn dilute the votes of any resident in other precincts. “When the first town meeting in the United States was held 380 years ago in Dorchester, prison counts were probably the last thing on the participants’ minds,” said report author Aleks Kajstura. “But today, the way the Census Bureau counts people in prison is a big problem for the principle of ‘one person one vote.'”

The towns of Billerica, Dartmouth, Dedham, Framingham, Ludlow, Plymouth, and Walpole each contain a precinct where 17% to 35% of the precinct’s representatives are directly attributable to the Census Bureau’s prison miscount, finds the report.

“For most of these Massachusetts towns, the Census Bureau’s prison miscount just wasn’t on the radar,” Kajstura said. “But fortunately, towns can make simple adjustments to keep the Bureau’s prison counts from distorting local democracy.” The report concludes that even though the problem of prison gerrymandering originates from the Census Bureau’s methodology, towns can take action to address prison gerrymandering.

Additionally, a resolution calling on the Census Bureau to solve the problem nationwide by agreeing to tabulate incarcerated people as residents of their home addresses in the decennial census is currently pending in the Massachusetts Legislature, and just passed out of Joint Committee on Election Laws. The new Director of the Census Bureau, John Thompson, recently stated that he has not yet decided how prison populations will be counted in the 2020 Census.

For Immediate Release: June 25, 2012

For Immediate Release: June 25, 2012