State officials tell counties to exclude prison populations from county level redistricting

by Peter Wagner, November 1, 2004

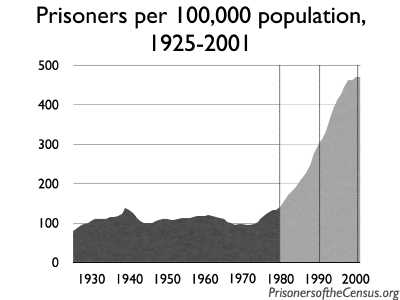

Previous articles have discussed individual counties in California and New York that have decided after public outcry to exclude incarcerated non-resident populations from their populations for purposes of local redistricting. This article looks at how 5 state legislatures and attorneys general have responded to the severe problem caused by the combination of an outdated Census Bureau “usual residence rule” and a rapidly growing population of prisoners incarcerated far from their homes. In four of these states, the state officials either required or encouraged the removal of prison populations.

The 1990 Census, was the first to see a large increase in the incarceration rate.

While no state has yet adjusted how prisoners are counted for state level redistricting, the practice of rural counties desiring to fix the census data prior to their local redistricting offers a valuable review of why prisoners should be counted in their homes and not in the prisons. The practice of excluding prisoners from local rural redistricting is completely consistent with this site’s argument that prisoners should have been counted in their urban homes. For example, the recently drawn New York City council districts would have included people in prison within their city council lines, but the readily available data from the Census did not allow that. At the same time, there really isn’t a question that urban prisoners do not have anything to do with county legislative matters in rural prison-hosting Franklin County. As three residents of that county explained:

“Franklin County has always excluded state prisoners from the base figures used to draw our legislative districts. To do otherwise would contradict how we view our community and would lead to an absurd result: creating a district near Malone that was 2/3rds disenfranchised prisoners who come from other parts of the state. Such a district would dilute the votes of every Franklin County resident outside of that area and skew the county legislature. We know of no complaints from prisoners as a result, as they no doubt look to the New York City Council for the local issues of interest to them.”(Rural citizens call for change in how Census counts prisoners)

These 5 state stories below illustrate how county and state officials have responded to the very large local harm to the One Person One Vote principle by using the only available after-the-fact fix: deducting the prison population from local redistricting to ensure that each district has the same number of local residents. Including prisoners in urban city council districts and restoring One Person One Vote on a state level is going to require either advance planning like that done or proposed in Kansas or Texas, or it is going to require the Census Bureau to update its outdated method of counting the incarcerated. But until then, it is worth noting that nobody thinks that the Census Bureau’s method of counting prisoners is a good idea for democracy.

Colorado

The state of Colorado requires counties to subtract incarcerated populations before conducting county redistricting:

“the board of county commissioners shall change the boundaries of the commissioner districts so as to create three districts as nearly equal in population as possible based on the most recent federal census of the United States minus the number of persons serving a sentence of detention or confinement in any correctional facility in the county as indicated in the statistical report of the department of corrections for the most recent fiscal year.” (Colo. Rev. Stat. sec. 30-10-306.7 (5)(a)

Jonathan Tilove described this requirement as having “sailed” through the legislature and explained the need for it:

In eastern Colorado’s Crowley County, commissioners are elected by the countywide electorate but must run from and live in a particular district. Counting inmates there, according to commissioner T.E. “Tobe” Allumbaugh, would have created a “prison” district without possibility of representation.

“It’s a little bit of a joke,” Allumbaugh said. “(The inmates) can’t vote. If they complain forever there’s a good chance I will never hear about it. There is a reason why they are in there, a reason why they don’t vote, a reason why they don’t pay taxes.” (Jonathan Tilove, Minority Prison Inmates Skew Local Populations as States Redistrict Newhouse News Service. March 12, 2002).

Mississippi

The Attorney General of Mississippi advised Wilkinson County that the Mississippi Code requires the exclusion of the prison population from county redistricting. Wilkinson County asked:

Concerning the mandated matter of redistricting of supervisor road districts in each county as a result of the 2000 Census, I have a private prison located in my supervisor district that houses daily approximately 850-900 inmates of the Mississippi Department of Corrections.

My question is, in redistricting the five supervisor districts of Wilkinson County, would the state inmate population of the prison be included in the census figures used to divide and balance the populations of the districts?

Miss. Code Section 47-1-63 states that persons incarcerated in a prison under the jurisdiction of the Mississippi Department of Corrections are not residents of the county where the facility is located, so would these same incarcerated persons be used in deciding the makeup of the county’s supervisor districts?

The Attorney General replied:

Our office has previously opined that inmates under the jurisdiction of the Mississippi Department of Corrections as well as inmates of local jurisdictions in local jails may not use the facility in which they are housed as his or her address for voter registration purposes. MS AG Op., Scott (October 27, 2000). They are not deemed “residents” of that county or locality, as incarceration cannot be viewed as a voluntary abandonment of residency in one locale in favor of residency in the facility or jail. For purposes of the Census, these individuals should have been counted in their actual place of residence. Such inmates should not be used in determining the population of county supervisor districts for redistricting purposes by virtue of their temporary presence in a detention facility or jail in the county, unless their actual place of residence is also in the county. (MS AG. Op. #02-0060, Johnson, Feb 22., 2002)

New Jersey

New Jersey law requires the exclusion of state prisoners from the drawing of school board districts. (N.J.S.A. 18A:13-8; Board v. New Jersey 2004 N.J. Super. LEXIS 361)

Virginia

Virginia law allows counties, cities and towns with Census populations that are more than 12% prisoners to exclude this population from redistricting:

In any county, city, or town containing a state adult correctional facility whose inmate population, as determined by the information provided by the Department of Corrections, on the date of the decennial census exceeded twelve percent of the total population of such county, city, or town according to the decennial census, the governing body of such locality may elect to exclude such inmate population for the purposes of the decennial reapportionment.(Va. Code Ann. § 24.2-304.1)

At least 3 (Sussex, Brunswick and Greensville) of the 4 counties in Virginia that are more than 12% prisoners took advantage of this provision to fix the Census Bureau’s data and protect local democracy. The fourth county, Buckingham County, did not reply by the time of this writing.

Florida

Florida is the only known exception to the pattern that when the issue of including non-resident prisoners within local redistricting is considered by a legislature or attorney general, the result is to recommend or require exclusion of the prisoner populations. But even there, the outcome of that exception proves the underlying rule: everybody who considers this issue recognizes that prisoners are not residents of the place where they are incarcerated.

In 2001, the Gulf County Attorney asked the Florida Attorney General if the county could exclude the prison population when dividing the county’s population between the 5 Board of County Commissioners districts. Unlike most states, Florida does not have a statute which explicitly defines a prisoner’s residence as the last pre incarceration address. The Attorney General replied that state law required the inclusion of the prison population within the district where the prison is physically located because the state law required the use of Census data. But even here, the Attorney General recognized that drawing a district that was almost one-half non-voting non-resident prisoners was not the preferable practice:

“However, as this question is controlled by state law, the Legislature may wish to consider whether Florida’s prison population should be included in population counts for purposes of redistricting.” (FL. AG. Op 2001-55)

Not willing to wait for the legislature to fix local democracy, Gulf County took more immediate action. They ignored the Attorney General opinion they had requested and subtracted the Census Bureau’s prison population when drawing equally sized districts of county residents.

“‘…. [T]here is no reason to count them,’ said Nathan Peters Jr., a longtime Gulf County commissioner.” (Jonathan Tilove, Minority Prison Inmates Skew Local Populations as States Redistrict Newhouse News Service. March 12, 2002)

Conclusion

A rapidly growing prison population and an increasing trend to locate the facilities far from the prisoners’ homes creates very serious problems for democracy. Legislative districts that are supposed to be drawn to contain equal numbers of actual residents start to vary widely in the number of actual residents when thousands of state prisoners from somewhere else are credited to the Census tract with a prison. This changes the weight of votes from different regions, in violation of the Supreme Court’s one person one vote rule. While the state-level impact of how the Census Bureau counts prisoners was only discovered immediately prior to the 2000 Census, we didn’t have estimates of the impact on specific state legislative districts until the first Importing Constituents report in 2002.

Because the impact was so much more obvious, local county governments have been struggling with this issue for decades. As this article illustrates, in the late 1990s and after the 2000 Census, state officials began to offer guidance on easy after-the-fact fixes: deduct the prison population from the local population for purposes of dividing political power in the prison county.

Half-measures are not ideal, but when it is already too late, they are better than no solution at all. Today, the next Census is more than 5 years away. That gives the Census Bureau more than enough time to craft a permanent, complete and proactive solution that changes the usual residence rule and counts incarcerated people where they actually reside: at home.

Note: Thanks to Matthew Widmer who did the bulk of the original research for this column. Bill Cooper of Fairdata2000, Christopher Muller of the Brennan Center, and Paul Wright of Prison Legal News also provided invaluable feedback and tips. I’ve started to list counties that I know exclude the prison population and welcome notice of other counties that should be included.