One judge calls our amici brief "particularly impressive and persuasive".

December 27, 2011

On Friday, Dec 23, a federal three-judge panel rejected a lawsuit seeking to overturn Maryland’s landmark “No Representation Without Population Act,” which counts incarcerated people as residents of their legal home addresses for redistricting purposes.

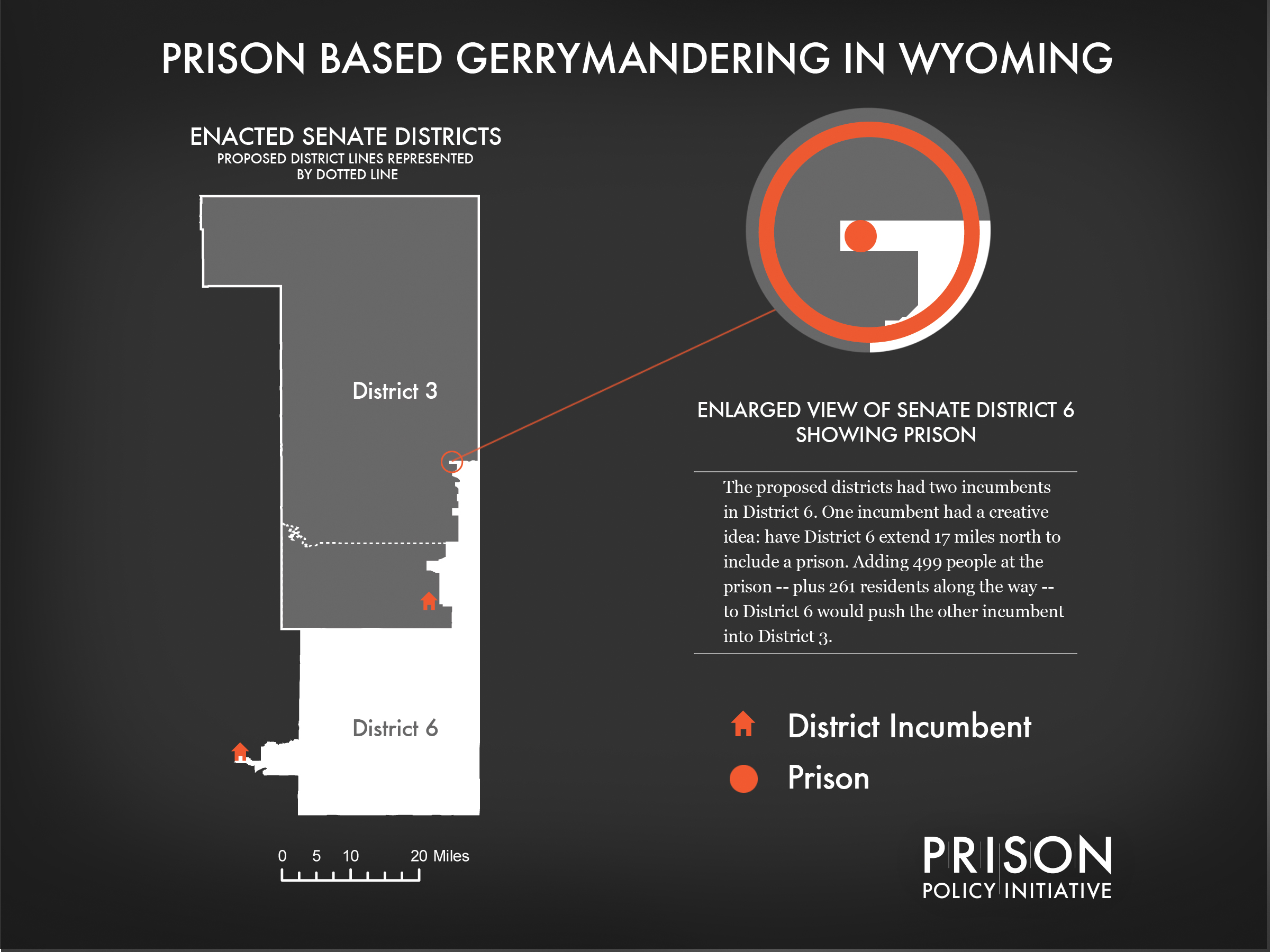

The Maryland law addressed a long-standing problem in the federal Census that counts incarcerated people as residents of the prison location, even though they cannot vote and retain their pre-incarcerated residences. For decades, using unadjusted Census data diluted the vote of every Maryland resident who did not live near the prison complex in western Maryland, and had a particularly negative effect on African-American communities that experience disproportionate rates of incarceration.

The Judges note that the No Representation Without Population Act they upheld was an important Maryland civil rights victory: “As the amicus brief … makes clear, the Act was the product of years of work by groups dedicated to advancing the interests of minorities.” (p. 20)

Other versions of Maryland’s law have since passed in New York, Delaware and California. Maryland was the only state to apply its law to congressional redistricting, and the first state to complete the process after passing a law. The Judges’ ruling that the law was properly passed and fairly implemented will encourage other states to pass similar laws and will hopefully encourage the Census Bureau to make their own changes in where incarcerated people are counted.

The Court issued its ruling late on the Friday before closing for the Christmas weekend, and just three days after a hearing on the evidence and oral arguments on Tuesday. The Court had promised a decision by the end of January, but quickly concluded that the lawsuit was without merit. The case, Fletcher v. Lamone, was a Republican-backed lawsuit that challenged the congressional plan proposed by the Democratic governor of Maryland. The suit raised claims of partisan gerrymandering and racial discrimination against African-Americans. Three of the claims attacked the No Representation Without Population Act as part of that otherwise unrelated lawsuit.

The Prison Policy Initiative, along with our colleagues at the Howard University School of Law Civil Rights Clinic, the ACLU of Maryland, the Maryland State Conference of NAACP Branches, Somerset County Branch of the NAACP, the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, and Dēmos submitted a friend of the court brief to make it clear to the court that the No Representation Without Population Act was protective of minority voting rights. (Our brief did not address the other claims in the lawsuit.) Judge Williams, in his concurring opinion, called our brief “particularly impressive and persuasive.” (p. 49)

The Court upheld the state’s congressional districting plan on all counts. While most of the 55-page opinion concerned other claims, considerable treatment was given to the No Representation Without Population Act.

The Court explained the law and its rationale:

-

Quoting the state’s summary, “the Act is intended to ‘correct for the distortional effects of the Census Bureau’s practice of counting prisoners as residents of their place of incarceration.” The court then goes on to explain:

“These distortional effects stem from the fact that while the majority of the state’s prisoners come from African-American areas, the state’s prisons are located primarily in the majority white First and Sixth Districts. As a result, residents of districts with prisons are systematically ‘overrepresented’ compared to other districts. In other words, residents of districts with prisons are able to elect the same number of representatives despite in reality having comparatively fewer voting-eligible members of their community.” (p. 9)

- The Court noted the critical importance of ending prison-based gerrymandering in local redistricting where the impact of a single prison can be the majority of a district. The Court discussed the infamous Somerset County example where a county commission district intended to be majority African-American was unable to elect an African-American for decades because the district contained a large prison and the African-American voting population of the district was too small to elect a candidate of African-American voters’ choice. (p. 9)

The Court explained that states are not required to blindly use the Census for redistricting purposes:

- Federal law requires Congressional districts to be exactly equal in population, but does not prohibit states from making improvements to the federal census data in establishing that population base. Federal case law allows adjustments to the data used for congressional districts. Although Census data is presumed to be a good starting point, the data can be adjusted to correct for flaws. These adjustments, however, may not be done in “a haphazard, inconsistent, or conjectural manner.” (pp. 12-13)

-

The Court found that The No Representation Without Population Act and its implementation by the Maryland Planning Department meets the standard, writing:

“The question remains whether Maryland’s adjustments to census data were made in the systematic manner demanded by Karcher. It seems clear to us that they were. As required by the regulations implementing the Act, … [the Maryland Department of Planning] undertook and documented a multistep process by which it attempted to identify the last known address of all individuals in Maryland’s prisons…. This process is a far cry from the ‘haphazard, inconsistent, or conjectural’ alterations the Supreme Court rejected in Karcher.” (pp. 16-17)

Because the No Representation Without Population Act was found to satisfy even the stricter standards applicable to congressional districts, the opinion bodes well for the constitutionality of similar laws that apply to state legislative and local redistricting, where governmental discretion to make adjustments in Census data is even clearer.

The Court addressed several other issues that come up frequently in discussions about ending prison-based gerrymandering:

-

Improving how incarcerated people are counted does not necessitate improving how other groups are counted. Plaintiffs criticized the state for reallocating incarcerated people to their homes, but not doing the same for members of the military or students in dorms. The Court called the assumption that these populations are all similarly situated to be “questionable at best.” The court explains:

“College students and members of the military are eligible to vote, while incarcerated persons are not. In addition, college students and military personnel have the liberty to interact with members of the surrounding community and to engage fully in civic life. In this sense, both groups have a much more substantial connection to, and effect on, the communities where they reside than do prisoners.” (p.18)

-

States should improve redistricting data where possible, even if it cannot be made perfect. For example, plaintiffs criticized the state’s reallocation because not all incarcerated people return to their exact prior address. The Court ruled:

“Because some correction is better than no correction, the State’s adjusted data will likewise be more accurate than the information contained in the initial census reports, which does not take prisoners’ community ties into account at all.” (pp.18-19)

-

The Court found that “although the Census Bureau was not itself willing to undertake the steps required to count prisoners at their home addresses, it has supported efforts by States to do so,” quoting the Census Bureau Director’s explanation that the new Advance Group Quarters data would

“enable states ‘to leave the prisoners counted where the prisons are, delete them from redistricting formulas, or assign them to some other locale.'” (p. 16)

The Court also addressed the main impetus for our brief, namely the plaintiff’s bizarre implication that a law passed with the intent of improving African-American voting rights somehow diluted African-American votes:

“Our review of the record reveals no evidence that intentional racial classifications were the moving force behind the passage of the Act. In fact, the evidence before us points to precisely the opposite conclusion.” (p.19)

For Immediate Release: June 25, 2012

For Immediate Release: June 25, 2012